Saving lives one word at a time

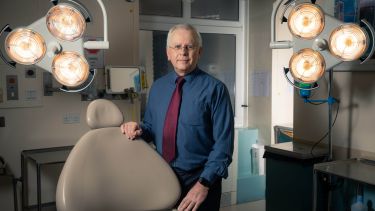

It’s not often that a single word saves lives. But when a member of the public approached Professor Martin Thornhill to understand how a heart infection had taken her partner’s life, the two of them instigated a small but transformative and potentially life-saving change to UK dental practice.

Ash Frisby lost her husband Myles to Infective Endocarditis (IE). During a routine dental procedure in October 2014, he became infected when bacteria from the mouth escaped into his bloodstream.

Myles had a replacement heart valve which put him at high risk of this fatal infection. Two weeks later the flu-like symptoms of endocarditis began. But with no knowledge of IE Myles and Ash thought nothing of it. Over the weeks that followed, his condition worsened with the development of a high temperature and overwhelming fatigue, but it wasn’t until 10 days before his death, in December 2014, that he was diagnosed with IE.

No-one expects to die from a routine visit to the dentist. The remit of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is to improve health outcomes for those using the NHS services and develop clinical guidelines for doctors, dentists and health professionals. These guidelines serve as an important resource for all health practitioners who use them to inform best clinical practice.

Infective Endocarditis (IE) can be fatal. And for a significant minority of people it can happen simply as a result of visiting the dentist. But in 2008 the lack of evidence on the effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis (AP) as a preventative measure for patients at risk of IE, led NICE to change the guidelines on the use of AP. Prior to 2008 guidelines had encouraged the prescription of antibiotic prophylaxis before dental treatments, however the change was a recommendation not to prescribe.

These were the guidelines that Myles’ dentist followed during his treatment. But when Professor Martin Thornhill first embarked on a study into the impact of the guideline change it wasn’t thought of as controversial. “Before we set out to do the research we actually thought that the NICE guidelines were correct and that antibiotic prophylaxis was unnecessary to prevent infective endocarditis,” Martin explains.

However, what Martin and his team discovered surprised them. , their study identified a significant rise in the number of people being diagnosed with IE following the guideline revision. This was alongside a large fall in the prescribing of antibiotic prophylaxis to patients at high risk of IE. By March 2013 this rise was accounting for an additional 35 cases in the UK per month.

Ash came across Professor Thornhill’s report whilst doing her own research into IE. She rang Martin and explained what had happened to Myles, telling him how her husband had previously been prescribed AP before dental treatment pre 2008. Following this, on one occasion when he had his teeth scaled without AP, he developed IE.

Before Ash contacted him Martin had already presented his findings to NICE. But the response of the general public moved the academic to re-engage with the issue. “In all honesty, it was the stories that I heard from patients and their families after we published the Lancet paper in 2015, that made us realise the importance of our data...” Martin said.

Martin helped Ash to construct a letter to Andrew Dillion, the Chief Executive of NICE, in the hope of persuading a guideline revision. Her letter highlighted the human cost of the guideline, supported by scientific understanding provided by Martin. Alongside this, Martin and his team produced an opinion piece in the British Dental Journal, the most read dental journal in the UK, in 2016.

They pointed out that, from an expert perspective, the risk of not giving antibiotics to patients at high risk of IE was far more damaging than previously presumed. This and a second opinion piece from Martin on IE were voted as the top two papers published in the journal in 2016. “Without Martin and his work, my communication with NICE would have accomplished very little” said Ash.

The partnership of Ash’s human story and Martin’s academic study was able to achieve something that wouldn’t have been possible individually. NICE inserted the word ‘routinely’ into the guideline, so it now reads

NICE highlighted that, “This amendment should now make clear that in individual cases, antibiotic prophylaxis may be appropriate…” This single word was, in Martin’s words ‘a major breakthrough’. Before ‘routinely’ was added, dentists were not allowed to prescribe antibiotics to patients at risk of IE prior to dental procedures. But now, if the dentist feels it’s necessary, if for example their patient is at very high risk of IE, they can make their own judgement and prescribe the potentially life-saving antibiotics.

So why are patients still not being prescribed AP? Simply put, their dentists don’t know about it. Ten years after the initial NICE guideline change, we have an entire generation of dentists who have no knowledge of its historic existence, let alone the controversies at play. Little has been done to publicise or clarify the advice, leaving those who are in the know in a state of confusion. “By introducing the word 'routinely' into the guidance, [NICE] removed the absolute rigidity of the guidance without clarifying how and when patients should receive AP. In the process they made the whole situation even more confusing for clinicians and patients alike,” said Martin.

News about the guideline review ignited interest from dental practitioners and cardiologists alike. “Universally, there is a very high interest in this topic and practitioners are keen to know as much as possible so that they do the best thing for their patients” says Martin.

But speculation leads to uncertainty. For Ash and Martin this cast an unnerving shadow over their progress which had the potential to render their efforts worthless. Many of those at risk of IE are not made aware of the complications of getting the infection nor the symptoms to look out for. Neither are they aware of the risk of infection presented by dental procedures. Had her husband been aware of these, Ash said he would have been better placed to ask his GP the right questions which might have resulted in a different, less tragic outcome.

This has directed Martin’s focus in the last few years, telling us, “people who’ve had dental procedures should be warned of the symptoms to look out for then more people might survive”. He’s now been around the world attempting to illustrate the personal cost and impact of IE and what clinicians can do to prevent it and diagnose it early. He’s spoken at international meetings of infectious disease experts and dentists, given lectures at the British Society of Endodontics and the British Society for Oral Surgeons, and spoken at cardiology meetings in the UK. Martin’s also investing time in a campaign for patients at risk of IE to be advised about the risk and be warned of the symptoms to look out for.

Through Martin and Ash’s work, dentists and cardiologists have become unified in their approach to infective endocarditis. In Martin’s eyes, “In some ways patients are in a better position to bring about change than researchers”.

Exceptional research is the backbone required to impact change but sometimes it needs a catalyst. For Martin, Ash was that catalyst and with more partnerships like this, we can have an even greater impact.

Filling the gap with the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Program

Without Martin’s work there would be little guidance for dentists about how to implement the guideline review. But what’s been done to formally fill the gap left by the change?

In Scotland, guidance to provide high quality dental care is governed slightly differently to the UK. The Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Program (SDCEP) provides advice designed to support dentists in providing high quality patient care. They’ve worked on the basis of Martin’s research and publications to fill the gap left behind by the guideline review.

Martin and his team published articles in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) and the British Dental Journal (BDJ) explaining what dentists should do in the light of uncertainty surrounding the guideline review. This provided the foundations for the SDCEP to formally issue similar advice to dentists on how the NICE guidelines should be implemented in clinical practice. Essentially advising dentists to give antibiotic prophylaxis to those at high risk, much like the American and European guidelines do.

Although originating in Scotland the advice itself has now been adopted nationally and approved by NICE themselves. Jeremy Bagg, the Chair for the Steering Group of the SDCEP has highlighted the “significant impact” that Martin and his collaborators, including Ash, have had in the development of these guidelines. This impact comes from a greater certainty for dentists about when to give antibiotic prophylaxis to patients which will ultimately have cost- and life-saving benefits.

Further information

Relevant publications

Funders, awards and key grants

- November 2014 and September 2015: Heart Research UK and Simply Health

- September 2016: Heart Research UK

- December 2016: Heart Research UK and The US National Institutes for Health

- November 2018: Delta Dental of Michigan and its Research and Data Institute

Related teaching

Written by:

Alicia Shephard

Research Marketing and Content Coordinator

University of Sheffield