The pesticide paradox: creating an acceptable killer

Pesticides are a key part of modern agriculture, but with often unpredictable effects damaging crucial elements of our ecosystem, where does regulation draw the line? Professor Lorraine Maltby explains how we can mitigate ecological harm by changing the way we think about our environment.

The butterfly effect

Imagine leaving the house tomorrow morning to find a dead beetle lying on the pavement. Unlike seeing a bird fall out of the sky, it probably wonãt set off instant alarm bells. In fact, itãs unlikely weãd even notice. That beetle, however, mightãve been responsible for recycling decomposing trees or even pollinating flowers during its short life.

Tiny differences in our surroundings like this have the potential to impact our lives in ways that are bigger than we realise. Far from being just a fragment of popular culture, the butterfly effect (or perhaps more fittingly in this case ã the beetle effect) has the potential to cause unpredictable changes to our environment, biodiversity and ultimately livelihoods.

Nothing quite illustrates this concept better than pesticides. The abundance of food that awaits us at every trip to the supermarket simply wouldnãt exist if not for these chemical concoctions destroying the unwanted organisms that harm crops. But their misuse can often have destructive consequences.

The problem is pesticides are damaging by nature. Professor Lorraine Maltby is an environmental biologist and ecologist from ôÕÑ¿øÝýËapp. She explains: ãPesticides are designed to be biologically active and can therefore adversely affect biodiversity and the benefits people derive from ecosystems. That means thereãs no such thing as a truly safe pesticide ã a safe pesticide is one that doesnãt work.ã

That begs the question: whatãs an acceptable effect for a pesticide and what isnãt? In using pesticides, can we ever be sure we wonãt be affecting the life around us?

Out in the field

Published by the European Food Safety Authority, the latest guidance document on the environmental risks of pesticides in aquatic ecosystems has drawn on scientific developments to improve risk assessment, including by Lorraine and her team at Sheffield.

The guidance has been applicable to any EU member state wanting to register a pesticide since 2015 and by March 2020 22 per cent of pesticide registrations submitted to the EU were not approved for use due to unacceptable environmental impacts identified using this guidance. Among its effects, the guidance has identified specific goals for protecting aquatic life as well as informed key decisions for risk assessors. It will steer us towards solving the puzzle of how to use pesticides to deliver the effects we want at minimal cost to the planet.

And itãs a new approach to answering the fundamental question of ãacceptable effectã in pesticides.

Since 2003, Lorraine has been building up an evidence base to better equip the world with dealing with these chemicals. As well as laboratory experiments and field investigations into how pesticides affect both single species and communities of different organisms, studies were also conducted in model mimics of freshwater ditches.

Using information gathered from literature and industry files, it was also possible to carry out modelling and analyses to predict the effects and sensitivity of these species to pesticides under realistic conditions.

Itãs this focus on working from a real-life framework that really matters, that has formed the basis for Lorraineãs work on the document.

Weãre using this information to try and understand three main things, what ecological systems provide us in terms of benefits ã known as ecosystem services ã how those benefits are driven by the types of organisms present and the things they do, then what potential effects pesticides have on those organisms.

Professor Lorraine Maltby

Professor of Environmental Biology

Weighing up these ecosystem services with the other considerations ã the human, the economic, the social ã and relating it to what people need and care about may at last allow us to start thinking about pesticides in a holistic way.

But the sheer breadth of EU-wide regulation poses a key problem for the specificity and relevance of current risk assessment. Risk assessors face a tricky compromise: itãs simply too time-consuming for every country to generate their own data specific to their needs and considerationsãÎ but this limits the types of organisms weãre able to monitor and means we might miss unexpected and unacceptable effects.

In order to turn answers into action, how do we extrapolate from what scientists measure at their lab benches to the creatures, plants and habitats weãre actually trying to protect?

The Daphnia in the jam jar

Pesticides have the collective power to eradicate all manner of pests that threaten the survival and growth of cropsãÎ and even those that donãt.

Runoff from fields and overspraying adjacent habitats, for example, can result in pesticides entering ponds, rivers or seas, causing fish population decline and biodiversity loss. This is happening across the world and is the key reason the EFSA guidance focuses on aquatic environments. Surely, then, such damaging potential warrants a tight and thorough regulation process?

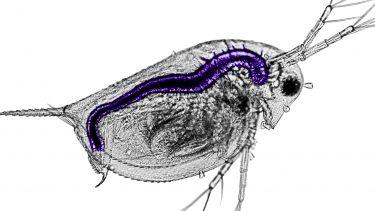

ãÎ Except how it currently works is to carry out individual studies on different species ã one on fish, another on a water flea called Daphnia, a third on green algae, for example ã then base risk assessment and protection decisions on these results. But Lorraine points out that testing just a handful of species isnãt going to give us the information we need.

ãThose studies are to protect the whole environment. Although that has its advantages in that itãs standardised and therefore replicable, the real question is what do you do with that information? What is it telling you?

ãThereãs obvious uncertainty with each of the extrapolations we make from this. Because of that, we might question how we can go from knowing the effect of a chemical on a little daphnia in a jam jar to all the invertebrates out there.ã

Tricky though the situation may seem, however, there are steps we can take to bridge the gap.

ãWhat weãre trying to do is to filter out the most harmful chemicals and effects as we go through different tiers of complexity in a very robust approach,ã Lorraine says. ãWeãre addressing those uncertainties that arise from the extrapolation and trying to peel some of them away at each level of regulation.

She elaborates: ãYou start with a very simple standardised approach where those really harmful chemicals are ruled out. So what youãre trying to do is filter out the ones in the lower tiers which would never be accepted for use because their effects are too damaging. We set out a regulatory framework where we can say: if these are the kinds of effects that these chemicals can have on these sorts of levels, beyond this level itãs not ecologically acceptable.ã

This tiered approach, having been validated for use in the document, is paving the way for improved pesticide regulation and, crucially, action. Among the methods utilised, investigating how to harmonise risk assessment across major EU legislation and how ecological theories can frame protection goals were just a few components to developing the approach.

As global biodiversity loss and environmental damage continue to increase, however, action is needed more than ever. But the biggest change will have to come from ourselvesãÎ

Societyãs decision

In the midst of a problematic global situation, where important trade-offs between human gain and environmental harm need to be made, simply advancing in our scientific knowledge may not necessarily lead to better management for the future. Lorraine says it ultimately comes down to us to decide how everything turns out.

She cautions: ãAt the end of the day, this is societyãs decision. Itãs society that can influence the decisions of the regulators and politicians. I think we have sufficient knowledge to manage and do a reasonably good job at the moment, but we need to change our mindset. As a society, we need to become more aware of how biodiversity is important to us and the multiple benefits we can get from ecosystems, and realise the implications of chemical use on those benefits from nature.ã

Even so, she is optimistic that a shift in how we think and act will increase peopleãs involvement and lead to a shift in the types of conversations weãre having too.

ãCurrently we tend to talk about how plants and animals behave and interact, not what that means in terms of providing goods and services to people,ã she says. ãItãs about having that conversation with people about why they should care about protecting the environment. Instead of thinking of ourselves as separate from it, weãre actually all in it together and we have to work together in order for us all to survive.

ãKeeping the conversation going and getting many different groups of people involved in it is really important,ã she concludes.

Yet at the beginning, Lorraine admits that her interest in the environment and its inhabitants didnãt extend to considering what it might provide us. She cites her career and research in facilitating the change in her personal outlook on the problem, now preferring to take a more social dimension instead of just going by the cold hard numbers. ãFor me thatãs the most interesting bit,ã she says resolutely.

ãIt gives me a good sense of satisfaction to know that weãre actually making a difference. And thatãs the key thing ã that our research makes a difference.ã

Helping to better our global situation is still an ongoing process for Lorraine: her current projects are extending her risk assessment approach to other chemical sectors as well as environmental issues, including understanding the impacts of chemicals under scenarios of future climate change.

In the end, though, what will make the real difference is our value of ecosystems and whether weãre willing to make the change.